by JONO MARTINEZ

Greek immigrants were among the last Europeans to make their way into the United States during the late 1800s. Toward the turn of the twentieth century, thousands of young Greeks fled to Utah to live what they would consider their first years of exile. Facing continued Turkish control in their own country, many of these people, young men and boys mostly, sought to live a life elsewhere with hopes of returning to a more promising Greece. (Papanikolas, 45)

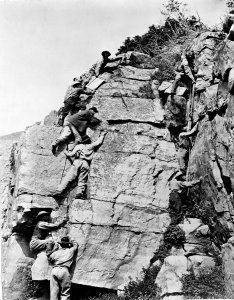

Finding solace in the American West, Greek immigrants quickly took to labor on railroads and mines as a means to survive. These men endured long, isolated seasons of strenuous labor with payment as low as $20 for a single month. Although California and Nevada would provide bountiful labor for immigrants, the railroads of Utah would be of special interest to them and would also tragically cost some of their lives. Among the places where extensive Greek contributions took place are the Carbon County mines, Murray-Midvale smelters, Bingham Canyon mines, Magna mill, Garfield smelter, and north of Ogden for railroad-gang work on the Oregon Short Line (later Union Pacific). (Papanikolas, 46-48)

On February 19, 1904, 24 men—16 of whom were Greek immigrant railroad workers—died in a train collision near the Lucin Cutoff crossing the Great Salt Lake. The Lucin Cutoff is a 102-mile railroad line in Utah that runs from Ogden to its namesake in Lucin. (“With Dead”) News reports at the time provided varying numbers of victims and gave inconsistent details regarding the details of the crash. By most accounts, the air brake system failed on the eastbound train, which contained a boxcar of black powder, and the locomotive collided with a dynamite-laden westbound train attempting to clear the mainline. (“Air Brakes”) The magnitude of the explosion was such that the adjacent small town of Jackson was destroyed and 1,000 feet of track were blown up, leaving an excavation 30 feet deep. One engine was blown over in the flat and almost buried in the salt earth; one of the drive wheels was found nearly a half-mile away. (“Dynamite Wrecks”)

An unidentified group watches a woman shaking hands with a railroad worker. Greek Archives photograph collection, 1900-1967, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.

The disaster would quickly gain the attention of local newspapers, with Ogden’s own Standard dedicating at least one piece a day of coverage for the weeks following the event. Accounts in the paper were graphic, with descriptions of decapitated bodies and scattered limbs. (“Dynamite Explosion”) Even the hailed New York Times would mention the half-mile radius of damage in its February 20 issue. The article listed by name the three American victims, but the immigrant workers were lumped into a single group with little to no recognition. While the tragedy was indeed covered in the news, the loss of the eight Utahns would ultimately overshadow the loss of Greek immigrant life. As The Salt Lake Tribune would make sure to mention on February 20, 1904, “A majority of those killed were Greek laborers, although many of the victims were English-speaking people.” The emphasis on “American” life over immigrant casualties in news accounts of the 1904 wreck ultimately reflected views that foreign laborers were expendable. (“Memorial Honors”)

Misfortune for the victims’ families only grew in the days following the accident. The designated coroner charged various undertakers, including Larkin & Sons, with handling the 24 bodies. Larkin opted to remove the bodies under his care to his own establishment in order to better prepare them for burial. This raised a protest from the assembled multitude of Greeks, many of whom had cousins and other relatives under the coverings inside the improvised morgue. They declared the bodies should not be moved. Richey, the other undertaker, later burned the blankets in which their bodies had been wrapped for transportation to the city. The Greek community had their own blankets that they wished to use instead, which were traditionally used for bedding. These were often hand-woven of superior material by them in Greece and brought to America with them. (“Dead are Brought”)

It was clear that there would be a long process in both identifying and treating the bodies, yet unique issues arose with regard to the extant language barrier between immigrants and local authorities who hoped to discover the cause of the accident. Two Americanized Greeks, John McCart and Arthur Mitchell, were sworn in as interpreters. Even so, they were unable to communicate much information to the authorities due to the conditions survivors were in. According to a story published in The Salt Lake Tribune on February, 26, 1904, “very little information concerning the accident could be elicited from the wounded Greeks.”

Other obstacles in the investigation came in the form of English-speaking witnesses who refused to give their full testimony. For example, Sam Courtney, the conductor of the water train, was questioned to no avail. Courtney’s hips and back were badly injured in the accident; yet, when he was asked who, in his opinion, was responsible for the makeup of the train and for the accident, he refused to make any statement. Ultimately, no blame would be placed on a single party and all persons interviewed would be absolved. (“Verdict of Jury”)

George N. Tsolomite, vice-consular agent for the Kingdom of Greece, arrived two weeks after the accident in Ogden. He then decided to contest each of the probate proceedings, which had just begun in Weber and Box Elder counties for the appointment of administrators in the estates of the Greeks who were killed in the recent railroad disaster at Jackson. (“Verdict of the Jury”) For many people at the time and now, it was evident that immigrants were misused as employees, especially those who could not speak English. Tsolomite’s involvement was to lessen aggravations felt by the families. Yet it was disasters like the one at Jackson and countless others that eventually energized immigrants to force employers to improve working conditions through labor unions. (“Memorial Honors”)

On October 22, 2000, nearly a century after the Lucin Cutoff tragedy, members of Utah’s ever-growing Greek community gathered in Ogden to witness the installation of a granite monument in memory of the deceased workers. (“Memorial Honors”) The tragedy and suggestion for the memorial were brought to the attention of the Utah Hellenic Cultural Association by Stella Kapetan of Chicago, who discovered the episode while researching her family history. (“Memorial”) This commemoration was seen by many as long overdue, considering that the majority of the men were buried without a headstone. For many, those Greek railroad workers who lost their lives are an example of the undervalued efforts and sacrifices undergone by immigrants in the United States of America. The memorial now serves as a reminder to both Greeks and non-Greeks of an otherwise downplayed moment in Utah history. Furthermore, their contribution as immigrants to help build the American West now receives the credit it has deserved.

Jono Martinez graduated in May 2017 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in journalism.

Sources

“Action of Greek Counsul,” Standard, March 1, 1904.

“Verdict of the Jury Judge Pritchard in Cut-off Disaster,” Standard, March 1, 1904.

“Coroner’s Inquest Continued to Thursday,” Standard, February 26, 1904.

“Inquest in Jackson Explosion,” The Salt Lake Tribune, February 26, 1904.

“Verdict of Jury in Cut-off Disaster,” Standard, February 26, 1904.

“Air Brakes Failed,” The Salt Lake Tribune, February 24, 1904.

“Dynamite Explosion Brings Havoc and Death,” Standard, February 23, 1904.

“Dead are Brought to Ogden Sunday,” Standard, February 22, 1904.

“With Dead of the Jackson Explosion,” The Salt Lake Tribune, February 22, 1904.

“Dynamite Wrecks Town,” The New York Times, February 20, 1904

“Memorial Honors Forgotten Victims of 1904 Railroad Tragedy,” The Salt Lake Tribune, October 23, 2000.

“Memorial,” Deseret News, May 29, 2000.

Papanikolas, Helen Zeeze. Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah State Historical Society, 1970.