In Park City, Utah, Ecker Hill may just seem like an ordinary mountain in the Wasatch Back to individuals. However, everyone may not know about how much historical impact it holds.

From the 1930s to the late 1940s, Ecker Hill was an original amateur and professional ski jumping mountain. The finest world-class jumpers traveled from all over the world to attend and compete in regional and national championships. The hill was just a handful of world-class ski jumps in North America. From 1930 to 1949, Utah would host national meets regularly, with approximately 10,000 people in attendance. (Roper)

Ski jumping in Utah started in 1915, where several young Norwegians settled in Utah, including figures like Marthinius “Mark” A. Strand and Axel Andresen from the Norwegian Young Folks Society. The group started hosting ski competitions in the intermountain area once a year at Dry Canyon, which is now considered the upper campus at the University of Utah. (Kelly)

However, in 1928, Utah Ski Club leader Peter S. Ecker wanted to attract more professional ski jumpers to competitions in Utah. The team decided that if it was going to attract the best ski jumpers in the world, it would have to build a world-class jumping mountain. With aid from the Rasmussen brothers, the team planned to establish a jumping facility at the Rasmussen Ranch near Parley’s Summit. Fast forward a year, the jumping enthusiasts—Ecker, Strand, and Andersen—created the site with the help of the Rasmussen family and local supporters. (Kelly) The glory days would finally occur, as the world-class jumping hill became a reality on March 2, 1930. The Park Record reported on March 7, 1930, that the Utah governor at the time, George H. Dern, named the hill after Peter Ecker, hence the name Ecker Hill.

The Salt Lake Telegram also reported on March 16, 1930, about competitor Ulland Fredboe expecting to break a personal record at the next tournament. These kinds of articles were extremely common during peak event times, highlighting different skiers and estimating whether or not they would break a world record.

Shortly after events started occurring, competition events increased at the hill. The Park Record reported on December 19, 1930, that a ski jumping event would be held on the first day of the new year. On New Year’s Day 1931, approximately 500 observers gathered on Ecker Hill to watch Alf Engen break the world’s professional ski jumping record. Engen jumped 231 feet, breaking the previous world record by two feet. On that same day, he smashed the world record again by jumping 247 feet. The Salt Lake Telegram honored that record in an article published on February 21, 1931, stating that it would be recognized as a national record. But that wasn’t the only time that Alf Engen broke world records. The world-class ski jumper set world records several times throughout the 1930s. His top mark was 296 feet, which was the longest jump ever recorded at Ecker Hill. (Roper)

There were many legendary names mentioned in ski history during the 20th century. According to a Salt Lake Telegram article published on February 23, 1933, there was a Champions Tournament that hosted competitive ski jumpers and athletes from all over the world. These names included Sigmund Ruud; Norwegian champion Torger Tokie; American record holder Reidar Anderson; and 1938 Norwegian champion Peter Hugsted (Roper)

In 1937, Utah hosted the U.S. National Ski Jumping Championship at Ecker Hill, led by Joe Quinney, the acting president of the Utah Ski Club. Alf Engen claimed the winning title while Norwegian Olympic champion Ruud followed behind. However, the U.S. Ski Association reversed the winning titles due to a technical ruling involving how house distances were calculated. (Roper)

While tournaments were held on Ecker Hill, two different jumps were used. The biggest take-off, known as “A,” was reserved for jumpers who jumped on a more professional level. The lower jump, known as “B,” was usually used for training and lower-qualified jumpers. There was sometimes a third jump that was reserved mainly for Alf Engen. It was much larger than the other take-offs so that the world-class jumper could pursue breaking world records. Jumps were also used not just by skiers, but toboggans as well.

Ecker Hill earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. On September 1, 2001, a permanent historical monument was set in stone, commemorating the historical ski jumping hill that still stands on the outskirts of Park City, Utah. The use of Ecker Hill has boosted Utah ski tourism to what it is today and is still remembered as the peak of ski jumping.

Primary Sources

Tom Kelly, “Summit County’s Skiing Origins, From Silver To Snow,” Park Record, March 11, 2020.

Frank Rasmussen, “Ski Tournament,” Park Record, March 7, 1930.

“Fredboe, Ulland Set to Break New Jump Mark at Ecker Hill,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 16, 1930.

Clark Stohl, “Ski Riders Reconstructing Ecker Hill for 1931 Tournaments,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 1, 1930.

“Ski Tournament New Year’s Day,” Park Record, December 19, 1930.

“Engen’s 247-Foot Leap to Be Recognized as National Record,” Salt Lake Telegram, February 21, 1931.

“Ski Riders Thrill Thousands at Ecker Hill in Holiday Meet,” Salt Lake Telegram, February 23, 1933.

Secondary Sources

Roper, Roger. “Ecker Hill.” Utah History Encyclopedia.

Collegiate sports are oftentimes regarded as rewarding experiences that can bring communities together and even ignite professional careers for some athletes. Being on a team surrounded by your peers can be a great time in your life. Unfortunately, the risk that comes with college athletics is a big one, and even more unfortunate, it often goes unrecognized. That was exactly the case in 1961 when the University of Utah’s wrestling team traveled to Powell, Wyoming, for a meet against the University of Wyoming.

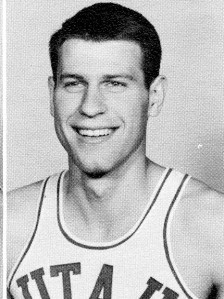

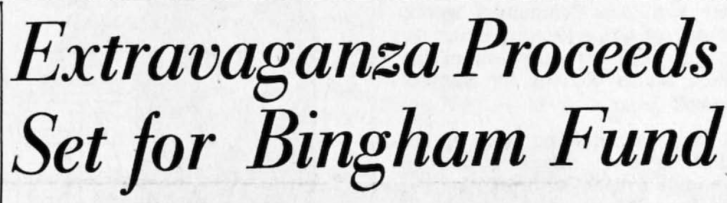

Collegiate sports are oftentimes regarded as rewarding experiences that can bring communities together and even ignite professional careers for some athletes. Being on a team surrounded by your peers can be a great time in your life. Unfortunately, the risk that comes with college athletics is a big one, and even more unfortunate, it often goes unrecognized. That was exactly the case in 1961 when the University of Utah’s wrestling team traveled to Powell, Wyoming, for a meet against the University of Wyoming. When Bingham died so unexpectedly, the school was unaware of the protocol in such a situation. It was a shock that someone so young and healthy could be there one minute, and gone the next. Bingham’s coach Marvin Hess referred to Bingham as someone “in fine health, perfect condition,” as the Arizona Republic reported on February 27, 1961.

When Bingham died so unexpectedly, the school was unaware of the protocol in such a situation. It was a shock that someone so young and healthy could be there one minute, and gone the next. Bingham’s coach Marvin Hess referred to Bingham as someone “in fine health, perfect condition,” as the Arizona Republic reported on February 27, 1961.