Barriers have existed for centuries either to protect or to keep people out. They have served as historical landmarks, such as the Great Wall of China, Belfast Peace Walls, or in this instance the Berlin Wall. The Berlin Wall was erected on August 13, 1961, as a result of conflicting ideologies between the East and West sides of Germany. (Fishman, p. 364) It later came to symbolize the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.

Three men stand on a post looking out at the Berlin Wall. Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Image is in the public domain.

In the aftermath of World War II two ideologies circulated Germany. Fishman wrote in History of Education Quarterly that the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was created in the Soviet Occupation Zone in October 1949. According to Fishman, the creation of the German Democratic Republic “was a response to the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, i.e. West Germany, five months earlier.” (Fishman, p. 364) The escalating tensions between these two ideologies erupted in the creation of the Berlin Wall, which was an attempt to halt immigration fleeing to the West on behalf of the German Democratic Republic. On August 27, 1961, the New York Times described the Wall from a helicopter view as “an unhealthy vein on a man’s arm.”

In the early stages of building the wall it was reported to be 25 miles long and strung with barbed wire. Once completed, according to Barksdale, the wall spread 96 miles long through the countryside and only 27 miles within Berlin. The New York Times reported on August 27, 1961, that the wall was mostly “dirty red-grey color with white splotches where Masons dropped mortar on the pavement.” The New York Times also observed that same day that “the Brandenburg Gate, once the chief crossing point between East and West, is deserted now behind its barbed wire fences.”

Closing of the border between the East and West sides of Berlin photographed at the Brandenburg Gate. The author of the photograph is Steffen Rehm. Image is in the public domain.

The impact of the wall was felt in all sections of life: work, relationships, and travel. The Berlin Wall separated families and halted almost all immediate immigration to the West. Violent confrontations between civilians and the police quickly gathered the attention of the world. The crisis in Berlin reached the crevices of local communities. The confrontations were featured in front-pages articles in local newspapers in the Provo Daily Herald and the Daily Utah Chronicle.

Local coverage in Utah focused on the tensions between these two polarizing sides in Germany and the responses from prominent leaders. For example, the Provo Sunday Herald reported on October 1, 1961, that communist police had strung barbed wire around Stienstueeken an isolated village and that, “In Berlin, East German refugees yesterday sought liberty or death in a grim game of ‘hide-and-seek’ with Communist border guards under orders to shoot to prevent them from escaping to the West.”

A few days later, the Provo Daily Herald reported on October 5, 1961, that there were two separate incidents that involved police gun fire at the border of the wall that same day. Fleming wrote about the first incident “Communist police first-fired [sic] four machine pistol shots today at a West Berlin electric worker laying a cable along the border when he wandered about the one yard into East Berlin.” The second incident involved an exchange of 40 shots. Fleming reported that occurred when, “Communist police began throwing rocks at a West Berlin police loudspeaker truck near the border area.”

Much of these violent exchanges prompted political leaders to speak out on these incidents. Mayor Willy Brandt of West Berlin had warned the Communist “to stop the shooting.” (Goldsmith) After a visit to the United States Brandt had a meeting with President John Kennedy via telephone. The Daily Utah Chronicle on October 10, 1961, reported on Brandt’s statement, “Rarely has the U.S. government committed itself so irrevocably than to the freedom of West Berlin.”

The Allies kept a close eye on Berlin watching these violent exchanges. The Provo Daily Herald observed on October 9, 1961, “There appeared to be differences among the Western powers as to the wisdom of continuing to probe for a soft spot in the Russian demands which call for abandonment of the Allied position in Berlin.”

The Berlin Wall illustrated an escalation of tension in a polarizing time in history. The wall obstructed the free flow of immigration and caused many East Germans to “plot their escapes and occasionally die in the trying.” (Newsom) These tensions are still seen today. The barriers still exist, except it’s no longer in a foreign land. The United States border has caused a similar polarizing tension between nations and citizens. Many immigrants have died in the Rio Grande attempting to flee to the United States or died of dehydration in the desert. Although the Berlin Wall has since been torn down, we still live in a divided world filled with walls.

Ivana Martinez is a junior at The University of Utah. She is majoring in communication with an emphasis in journalism.

Primary Sources

Joseph E. Fleming, “Reds String Barbed Wire Around Isolated Village,” Provo Sunday Herald, October 1, 1961, 1.

Joseph E. Fleming, “Gunfire on Border Stirs Crisis in Berlin; Mayor Brandt Heads for U.S.,” Provo Daily Herald, October 5, 1961, 1.

Phil Newsom,“Story of Human Tragedy Seen in Berlin,” Provo Daily Herald, October 5, 1961, 12.

Steward Hensley, “U.S., Allies Study Move In Berlin,” Provo Daily Herald, October 9, 1961, 1.

Joseph E. Fleming, “Brandt Warns Against Concessions; Mayor Says U.S. Firm on Berlin,” Provo Daily Herald, October 9, 1961, 1.

Michael Goldsmith, “W. Berlin Mayor Brandt Warns Soviets:‘Stop The Shooting,’” Daily Utah Chronicle, October 10, 1961, 1.

Joseph E. Fleming,“Allies Say Red Mobilization In East Germany Grave Threat,” Provo Daily Herald, October 10, 1961, 1.

Secondary Sources

Barksdale, Nate. “How long was the Berlin Wall?” History.com, September 1, 2018.

“Berlin Wall Built,” History.com, August 13, 2019.

Fishman, Sterling. “The Berlin Wall,” History of Education Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1982): 363-70.

“Berlin Wall,” Encyclopædia Britannica, November 29, 2019.

“The Wall Marks Blotch in Berlin: Red’s 25-Mile Slash Across City Viewed From the Air,” The New York Times, August 27, 1961, 8.

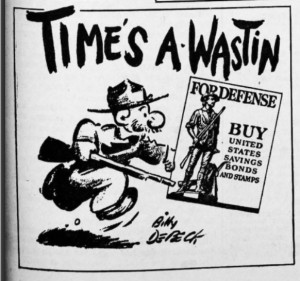

Dr. Dilworth Walker, dean of the U’s school of business, announced the opening of a campaign to raise $2,500 for the war chest in a Utah Chronicle article published October 28, 1943, urged all university students, faculty and employees to contribute to the Salt Lake County War Chest.

Dr. Dilworth Walker, dean of the U’s school of business, announced the opening of a campaign to raise $2,500 for the war chest in a Utah Chronicle article published October 28, 1943, urged all university students, faculty and employees to contribute to the Salt Lake County War Chest.

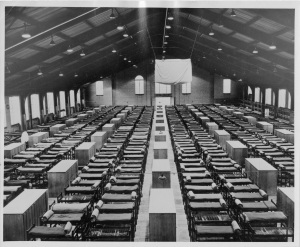

As reported by the Salt Lake Telegram on Tuesday, January 11, 1943, Lieutenant Tova L. Petersen, a recruitment officer for the WAVES and SPARS, arrived in Salt Lake City to interview applicants. Just one month later the first Utah women would enlist in the military.

As reported by the Salt Lake Telegram on Tuesday, January 11, 1943, Lieutenant Tova L. Petersen, a recruitment officer for the WAVES and SPARS, arrived in Salt Lake City to interview applicants. Just one month later the first Utah women would enlist in the military.